“It required a rib, apparently.”

HEATHER CHRISTLE

Interviewed By: Natalie Tombasco

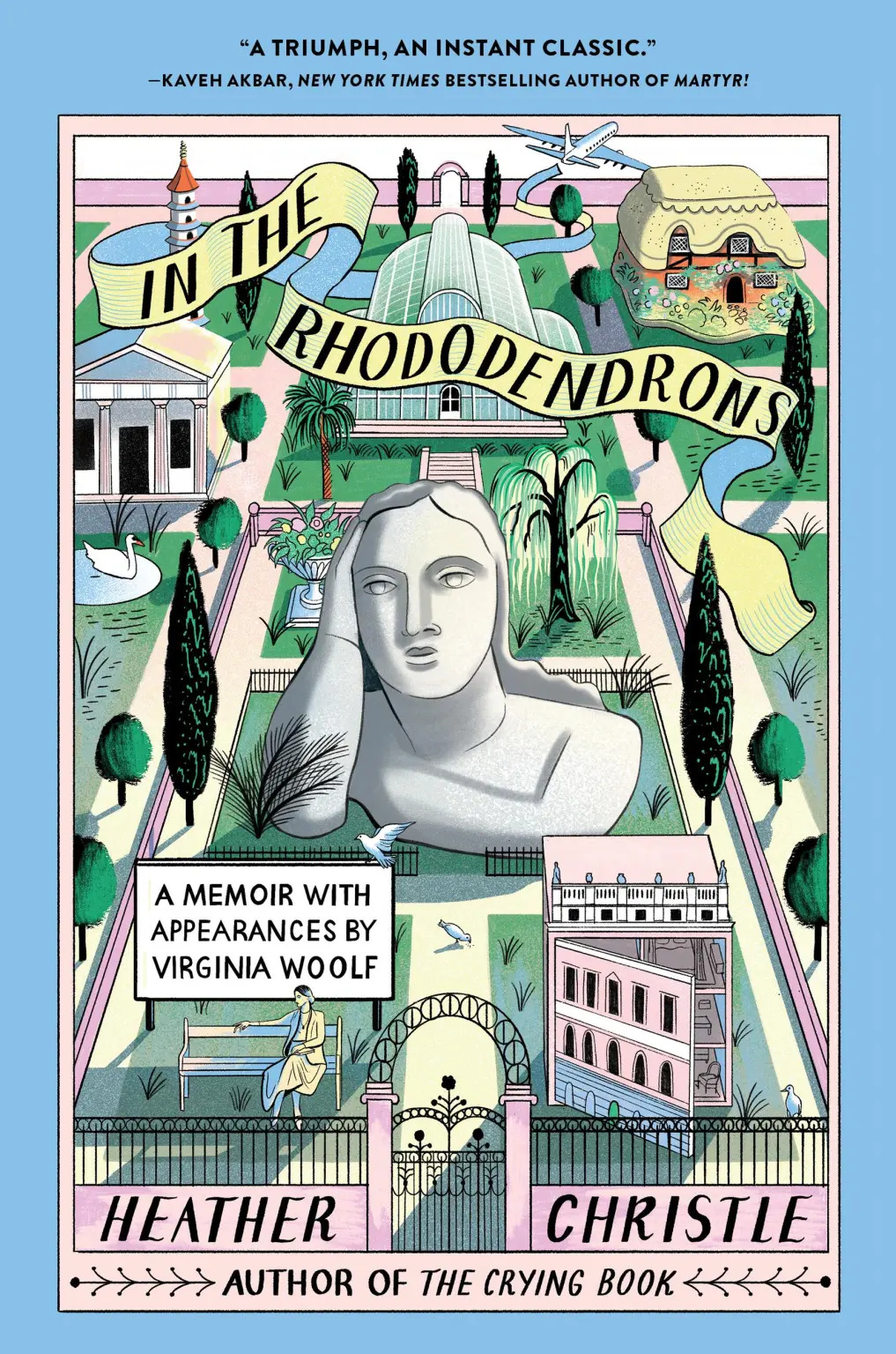

When you last spoke with Divedapper (nearly a decade ago!), Heliopause had just been published, and you were just starting a new venture in prose, which would ultimately become The Crying Book. I’d like to begin by asking a little about your second work of nonfiction, In the Rhododendrons: A Memoir with Appearances by Virginia Woolf, which was released this past April. It’s a hybrid lyrical and researched memoir that entwines the parallels of shared trauma between mother, daughter, and Virginia Woolf.

In an essay, where you describe how you lost a rib in the composition process, you include a Tony Tost line, “I don’t know how to talk about my biological father, so I’m going to describe the lake,” and remark, “I had so many lakes. I began the process of draining them.” Can you speak about your intentions behind this project and how you managed to balance the personal subjects with the more indirect wanderings to various “lakes?”

When I first started writing In the Rhododendrons, I thought it was going to be an essay about Kew Gardens and my family’s connection to it. I also thought it would develop similarly to The Crying Book, where I’d write a little prose poem about crying, and then another, until a book emerged, but the more I researched, the more I realized how much I had to learn about subjects far beyond Kew. As I worked with my very patient agent and editor, the Gardens remained a crucial location for the book, but I discovered that the book’s center was about the relationship between myself and my mother, myself and Virginia Woolf, and the relationship of all three of us. It was shifting to England, our lives and histories—both personal and public.

Mm-hmm. There are a lot of layers there.

Yes, and there are dynamic exchanges between those layers: particular places in England, and the idea of England itself, and how we think about writing the complicated story of ourselves in relation to real places and our ideas of them…

Woolf is “geographically proximate” and literary mother of sorts—a trusted companion for this pilgrimage to document and reconcile the past by investigating diary entries, photo albums, and archives to do so.

Woolf is a kind of mother and trusted companion. I think that’s true. But she’s also someone who can let you down. I feel an immense affinity with so much of her work, and with her rhythms of thought and language. It’s easy for me to get carried away by that rhythm. But then sometimes you think that you’re riding along in the company of someone you understand, but suddenly, you look over, and their horse is now on the racism track. You’re like, “Whoa, I didn’t know we were going there, Virginia!”

I guess what you’re referring to is blackface, right?

That’s one part of it, yes. There are other examples, too. The opening scene of Orlando has some rough material. Her classism is also pretty wild. I’m fairly certain she would not approve of me in all kinds of ways. Even though I very much needed her to be my companion in this journey.

Many people visit Emily Dickinson in Amherst or Ernest Hemingway in Key West, but this is an extreme case of literary tourism. Many of Woolf’s works can be read with the concept of travel or mobility in mind. Mrs. Dalloway is a flâneuse, The Voyage Out’s mythical ship sails toward self-discovery, Orlando’s journey spans centuries, and in To the Lighthouse, a beach house serves as a fixture as a decade is distilled in twenty pages or so.

Your memoir acts as a travel narrative, too, despite the irony of being confined to a closet to write during the pandemic and literally getting knocked in the head with A Room of One’s Own by your cat! You recount many visits “across the pond,” perhaps, as a way to investigate your biological mother’s etiquette and beliefs, her Englishness—a history and colonial legacy that’s often fetishized, erased. “I did not know how to love my mother without also loving her country,” you write, “Neither took kindly to being questioned. Conflict was impolite.” I’m curious about your engagement with travel to the UK as a journalist and a daughter.

The lines became blurred. Writing it was psychologically and sensorially intense, intellectually and emotionally demanding. It required a rib, apparently (laughing). For a long time, I did not have enough money to go to England, so I carried on an imaginary relationship with the place. I accessed it through family stories and reading books. When my financial circumstances changed, I was genuinely surprised to suddenly be able to afford to visit this place that occupied my mind. Some of the emotional torque of the book is about that astonishment. I couldn’t believe this place was real. I could finally touch it. Being close to Woolf, touching the threads that she knotted together for the pages of “Kew Gardens—”

I didn’t know that story existed, so thanks for introducing me to it.

Yeah, no problem. I think it’s magnificent. I have a great deal of admiration for her work across her life, but there’s something particularly magical about some of the early short stories. “A Mark on the Wall” and “Kew Gardens” are two of my absolute favorites. You feel her mind working with language in a mode of delight and discovery.

In considering literary tourism, I’m amazed by physical artifacts and their links with the past. It seems impossible that objects continue to exist in space, across time, and that we can then encounter them ourselves. When I was working on the book, I walked to Woolf’s country house in Rodmell, which is run by the National Trust, and the next day to her sister’s house at Charleston Farm. (In the Rhododendrons says more about those visits, but I recently wrote a bit about Charleston in particular for The Believer.) Woolf herself was also a literary tourist and thought about the subject over many decades. Early in her career, she wrote about going to visit Haworth—the Brontë family’s home, and then—for example—in the 1930s, she was still thinking about what so-called “Great Men’s Houses” tell us about their lives and work.

So, Kew Gardens is just outside London. I find it interesting how the public parks and botanical spaces of a city—Boboli Gardens in Florence, Luxembourg Garden in Paris, and Central Park in Manhattan—are emblematic of national identity and pride. Kew Gardens boasts its diverse and bountiful plant collection and architectural features like the Great Pagoda, which draws from Chinese influence. Your attention moves from the arches to the gates to the walls of Kew to consider borders, migration, and “the violence of imperial extraction.” You also explore Kew as an example of what Foucault describes as a “heterotopia.” How do you feel it fits this idea, and what pulled you toward it?

Kew Gardens, as an example of a heterotopia, is a space that’s apart from the society around it. It’s set off, quite literally, as a walled garden. It requires ceremonial access, which is especially true if you go into the archives. A library is another heterotopia. It’s apart from, but shaped and informed by the society that made it. Kew Gardens says much about the UK—its historical narrative and current moment. Kew Gardens was originally a royal garden, and over time, it transformed from a leisure space where royalty dabbled in horticultural experiments into something more scientific in focus; a scientific mode driven by the economic impulses of empire and extraction. It began to serve as a hub for the management of the agricultural and horticultural side of empire.

Jamaica Kincaid writes about this beautifully and sharply. I’m a huge fan of the way she writes about gardens generally. She also hates Vita Sackville-West, which gives me great pleasure because the more I worked on this book, and the more that I learned about her, the more I was like, “Oh man, not her again.” I do understand the importance of Sackville-West as a queer icon, but/and I’m thankful to people like Jamaica Kincaid, who are also like, “Let’s hold this person to account.” There’s some accountability required there.

Right. The sections with Jamaica Kincaid bring forth differences between cultures and landscapes. It reminded me of Wide Sargasso Sea’s juxtapositions where you have the “extreme green” lushness and colorful warmth of the Caribbean (mango leaves, red hibiscus, jasmine, orchids…) contrasted by the “rosy pink in the geography book map” of England which is this far-off dream of Antoniette’s: cold and barren hills covered in swans and snow that act as a signifier for whiteness. Kew’s Palm House seems to be a symbol of a way to preserve and exoticize plant life that wouldn’t be able to exist in its hostile winter climate, creating this tropical wonderland.

Yeah, well, the garden becomes a place to display dominion, right? To say "we have control over all of these regions," which is represented horticulturally. Kew Gardens is an interesting place. They did a lot of work, as many institutions did in the summer of 2020, to engage with their colonial legacy and to reckon with the violence with which materials were extracted. There are plant specimens from Kew or the British Museum that were acquired through the labor and knowledge of enslaved Black people. But even this mild institutional work of reckoning that was starting to happen was enough to set the right wing off and demand that it be shut down.

Wow.

They definitely didn’t want Kew to get to the point that Kim TallBear points to, of asking what is being restored to the people who had been taken from? The answer in these cases is not nearly enough yet. But even that is enough to make the right wing come in, freak out, and try to shut things down. The same thing happened with the National Trust, the UK conservation charity who have worked to tell the story of the links between these grand estates that people love to go and visit on the weekends, and the source of the wealth that made those houses possible. A right-wing group with opaque funding has tried to take over the National Trust council, repeatedly, because they feel that learning about the actual history of the great houses is “anti-white” and—perhaps even more importantly—interferes with people’s ability to enjoy their tea on their nice day out in the country. They are so sensitive!

I think the reckoning involves exploring the undeniable legacy of Woolf, alongside the messiness and complexity of who she was in her time. The existence of both sides is really fascinating.

Yeah. I think that that’s a huge part of what the book wants to do: look at both sides of things, or look at moments, or look at particular places that seemed to have irreconcilable differences. Not to work to lay those differences to permanent rest, but to gaze at both of them in a way that provides a dynamic instability. That means we have to keep looking and keep reckoning and seeing the ways in which the past continues to affect the present—and potentially our future. That’s true of the history of the British Empire, and that’s true of my own story, and my understanding of my family’s story as well. I’m not done learning. I’m not finished perceiving new tensions, new flashes of what could have been—or could yet be—otherwise.

In considering Woolf’s craft, I find a deep kinship with her writing, which, by some trick, defies time and space. I’m fascinated by her observations of human relationships and motivations, gender norms, explorations of consciousness, innovations to the form, etc. On a line level, I get lost within the long-winding syntax and astute imagery that cuts to the essence of something. It’s a masterly playful prose that reveals a keen eye and ear for lyricism. It’s funny, I’ve always wondered why she chose to make Orlando a poet instead of a fiction writer. Do you have any insight into Woolf’s relationship to poetry, or can you perhaps share the poetic qualities, or a specific passage from one of her texts, that you’ve admired?

Yeah! I think “The Mark on the Wall” is a great instance of poetic prose. I could imagine a version of it published as a prose poem today. It has that flitting movement of thought that diverges from the mark on the wall, but then it returns to it. Woolf is such an excellent practitioner of meaningful divergence. She believed in writing that followed the rhythms and musical qualities of language. She’s a far better poet than Sackville-West ever dreamed of being, despite the fact that Woolf did not break lines.

She made her character of Orlando a poet because Sackville-West was a poet. Sackville-West was practicing a kind of poetry that was deeply conservative and tied to the idea of the preservation of an imaginary past over which she was lord and master. I think Woolf was practicing a kind of poetics that put her and language on equal footing. In any case, she was involved in poetry in other ways as well; she and Leonard Woolf published chapbooks by poets at the Hogarth Press. In the UK they call them "pamphlets," which I kind of love. She was also friends with T.S. Eliot, but snobbishly—she looked down on him in all kinds of ways. It’s so hard to be an American poet around Woolf!

(Laughing) It is! Shifting slightly to your first memoir, The Crying Book, it has a similar textual tapestry that expertly weaves the phenomenon of crying alongside personal narratives, meditations on grief, factoids, scientific information, and cultural analysis. You share the best and worst domestic spaces to cry in (“A kitchen is the best—I mean the saddest—room for tears”) and the differences between basal, irritant, and psychogenic tears. When working with many threads, what organizing principle do you use? How do you find poetry and essay writing feed into each other?

Writing poems has trained my associative capacity to a greater extent than is probably warranted by the world. It can go into overdrive. That’s the danger in writing creative nonfiction. You can get from any one idea to another, eventually. It’s not that hard! Eula Biss has referred to Robyn Schiff’s idea of “bound association,” which is to say that it’s not enough to just endlessly associate. Instead, we have to think: what constraints are we going to place on this? The associative movements have to possess enough velocity to keep the whole thing aloft.

For me, it means behaving in this fashion where, at first, I’m endlessly associating. I’m spinning through time and space. Things are being pulled into my orbit. Things are also spilling out from myself. There’s this great sense of objects orbiting. Some of it is natural material, some of it is space junk. Some of it is my friend who’s communicating with me. I think in this metaphor my friends are astronauts?

Astronauts make solid companions.

With the editing process, I do a lot of indexing work, where I track things that reappear. I make lists of those recurrences. Most of them I already know, but occasionally there will be something I discover. The repetition of rhododendrons was not at first visible to me, for instance, in the memoir. Once I have my list, I look to see which threads are absolutely material; which threads are so intertwined with others that they become structurally necessary; which things are truly orbiting and interacting with some other strands there, but not enough to justify their ongoing presence in what will become the published book.

I loved your metaphorical use of the stereoscope in In the Rhododendrons and the lachrymatory of The Crying Book, where you liken each blocky vignette to an individual tear gathered into the whole of the book. To me, that’s where a poet writing prose illuminates a narrative. Why were either the stereoscope or the lachrymatory useful metaphors to view your subjects and think of structure?

I think this goes back to that idea of irreconcilable differences. With a stereoscope, you are looking through the lenses at two slightly different images. Like, when you’re looking through a View-Master—the red plastic toy that has the circular disc—your left eye is looking at one image, your right eye is looking at another. There are two very slightly different perspectives on the same scene. Because of that, you experience a sensation of depth, because it’s also how we tend to experience the world. We have one perspective from this eye, and one perspective from this other eye. We don’t experience them generally as two separate things. Layering them together allows us to perceive depth.

Very cool.

Binocular rivalry is an incredible phenomenon that can be induced in people when they look at not slightly different scenes, but irreconcilably different ones. The experimental images that people use to explain the concept are usually an image of a house for one eye, and an image of a face for the other. If you look at them at the same time, a lot of people will either see just one as dominant, or they will switch back and forth between the two.

I have always experienced what’s called piecemeal rivalry, where my brain puts together a patchwork of the two. That means that I’m seeing an eye in the window, and a mouth in the door, but it’s also unstable and dynamic, and changes as I move my gaze around. I feel like there’s a useful metaphor there that poets are accustomed to looking and seeing at least two different things at once—seeing the likenesses between unlike things. It’s one of the crucial acts of perception that we can practice.

This is intriguing considering how closely released In the Rhododendrons and Paper Crown are in time. I certainly find similar attentiveness to specific material, such as miniature villages, a restaurant scene with friends, archives, View-Masters, “the big bibliography / in the sky,” and surrendering your belongings in “Suggested Donation.” It’s fun to see these texts communing, exchanging, transforming reality into poetry.

I’m sure there was a huge relief to depart from the “excess in grief” of memoir to your more poetic mode. I enjoyed the lines in “Shelter in Place” that go: “When you write a book you must not / forget to build a door you can use / to get out or else you will die there.” Another self-aware example comes in “My Visual Aid is a Timeline” when you note, “If I outline my body / on the same wall every day / I am writing a moving new memoir.” I loved those moments where you break the fourth wall, where I’m able to witness how process overlaps.

Yeah. I would not feel at ease—fair or honest—if I were to forbid myself to write about miniature villages or View-Masters in a poem, just because I had written about them in prose and vice versa. There are inevitabilities in recurrence. Reading so much Virginia Woolf all at once made me see her “hither and thither” so clearly. She’s “hithering and thithering” all over the place. That phrase appears constantly, and it aptly describes her style. There’s a lightness in the words that’s equivalent to the way that her mind flutters over things.

Another inevitable recurrence is this line from “Suggested Donation:” “I run the deer’s / archive. It’s very / light work.” This made me laugh for obvious reasons, but it also fastened nicely to the final scene from In the Rhododendrons when you break into the grounds of Knole House.

I love that connection! Knole is this grand estate where Vita Sackville-West grew up. Virginia Woolf used it as one of the central places in Orlando, and for the ending scene. I felt really determined to make In the Rhododendrons end there at Knole as well—even though I had to break in with some friends, who thankfully, were game. I remember there were all of these deer, and it was rutting season. The stags were very edgy. It was a little bit of an unnerving night, surrounded by horny deer bellowing at each other through the dark….

But, to come back to your question about the deer archive—I am devoted to working in collaboration with language. I try not to let our immediate physical surroundings become too dominant, but sometimes language and I are sparked by them. So, the deer—at Knole, at my Ohio garden—will show up in the poems. The “deer archive” is obviously imaginary outside of the setting of the poem, but inside the poem, this idea takes on its own reality. That got me wondering about the actual deer I was looking at: what would happen if deer kept diaries? They would be very short, right? Once I reached that point in the poem where an imaginary text by a deer was produced, it seemed like the natural consequence would be that there would be an archive, and you’d need someone to run it. And it’d really be a great job!

(Laughing) Of course! This speaks to your poetics and how there’s a turbocharged imagination that demands its own logic. This is random, but I was watching this stop-motion film, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, between reading Paper Crown and Heliopause. Marcel has this imaginative resourcefulness that is charmingly humorous. He uses a tennis ball as a vehicle to speed around the house, human toenails for skis, and sticky honey to walk along the walls to obtain what he needs to survive in a vast world. There’s a defamiliarizing wonder to the film that transforms ordinary objects and offers a unique perspective that reminds me of your poems, sharing this same wide-eyed curiosity and playfulness.

For example, poems like “People Are a Living Structure Like a Coral Reef” have been enjoyed for the “anthropological interest” the speaker takes in the human species as if they are an outsider looking in. This “complete wonder” is present in “The Running of Several Simulations at Once May Lead to Murky Data” where speaker plays with proportions to enact this youthful marveling at the mundane world. I remember first reading The Trees The Trees, and immersing myself in the fragmented, visual experiments happening on the page. They were somewhat plain in diction, familiar, but also dreamy and enchanting. Similar to fairy tales, though, there was treachery and a feeling of slight paranoia. Something lurking in the dark woods. This is more of an observation, but it seems like those imaginative and experimental qualities are mainstays across collections. How do you see your work developing, altering, or staying the same from one book to the next?

Thank you for all of the kind things you’ve said. I think imagination is probably the most constant concern throughout the books. It’s what I have most faith in. It can also get me into trouble. My acts of playful imagination can get in the way of my actually being in the world as it is, but then there are times when it enhances that ability.

And then there are the changes. The Difficult Farm was written, improvisationally, one word at a time. With The Trees The Trees, I was reading a lot about cognitive linguistics and wanted to explore the possibilities of syntax. It was still improvisational, but with a recipe of adding a double copula here, or an idiomatic turn there. I was trying to figure out the relationship between three aspects: form, breath, and polysemy. I was focused on the multitude of meanings that could be progressively created through a formal decision to separate words by space or breath. In What Is Amazing, I was working faster, composing the lines so things were more smashed together. I started to allow myself to be directly intertextual and semi-autobiographical in Heliopause, which I think led to The Crying Book. I hadn’t forbidden myself to be personal before Heliopause, but I didn’t have a strong appetite for it. Research entered immensely with the memoirs. It’s difficult to ascribe some kind of procedural consistency to Paper Crown, but I think bringing many of those modes to the table—the practice of improvisation, the occasional autobiographical moment, the interest in syntax, commitment to imagination—it became possible to create something playful, but still touched by history and its shadows.

Speaking a bit more to how your poems share a hyperfocus of language—the syntactic, phonetic, semantic play—an uncovering of etymologies, and tinkering with clichés and idioms. You write, “Some words take shape / when spoken or thought of / aloud; cup, for instance, / corresponds so exactly with the object it names / that your mind can fill / …. my skull / is lined with shelves.” There’s levity as well that reminds me of the work of Harryette Mullen, Matthea Harvey, Russell Edson, and James Tate. Where does this linguistic exuberance stem from? Is there a poem that you love that toys with language?

I've been thinking about why I write—not in a despairing way but genuinely like, “why do I do this?” That’s probably in part because of all the think pieces about AI and Large Language Models (LLMs). To be totally frank, how I write is really similar to how LLMs function. I’ll write a word, think about all of the words that could potentially come next, given the basic constraints of the English language, and then I’ll choose one of those options. (Coding people would see this process as creating and working with what they call vectors, I think.) So, “why do I do this?” Not because I need to differentiate myself, or humans, so much. There’s a part of me that gets suspicious about that. Leif Weatherby has written about the endless need to differentiate by saying what machines can and cannot do in Language Machines: Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I still find myself returning to Jack Spicer, who was a foundational figure for me. Check out the recordings of his Vancouver lectures, or if you want to read them, you could get his Collected Lectures. He speaks about this practice of dictation and this idea of poems coming from outside. That’s what it comes down to for me. When I am making a poem, I really do have the feeling that language and I are working together to receive the poem. Jack Spicer also uses the metaphor of the poet as a radio receiver.

Oh, cool.

Yeah, and somebody in the audience is sort of like, “Well, wouldn't that make everyone the same? We’ll all write the same poem if we’re just receiving messages.” Spicer continues the metaphor, talking about differences from one radio set to the next. I think about this as I happen to be constituted in this moment, embodied here, with this particular history and particular set of attractions to certain words and ideas about how a poem could be. It matters which material I’m clearing away as I’m working to receive the poem; the shape language and I are working towards by moving to the side to allow the poem to come through.

I love this idea of receiving the poem as radio frequency alongside LLMs. I feel like it’s one of the more positive takes on artificial/human intelligence and role on art.

Yes. Another aspect of my poems you brought up is levity—that’s true. For poetry, I’d probably add Dara Barrois/Dixon, Mary Ruefle, Sasha Debevec-McKenney and Chessy Normile to the names you’ve mentioned. If it’s okay to go out a little past poets, I often think of this Bill Murray interview. He’s talking about comic pitch, and he says—hang on, I’ll read it to you:

“Well, obviously a lot of it is rhythm, and as often as not, it’s the surprising rhythm. In life and in movies, you can usually guess what someone is going to say. You can actually hear it before they say it, but if you undercut that just a little, it can make you fall off your chair. It’s small and simple like that. You’re always trying to get your distractions out of the way and be as calm as you can be, and emotion will just drive the machine. It will go through the machine without being interrupted, and it comes out in a rhythm that’s naturally funny, and that funny rhythm is either humorous or touching. It can be either one, but it’s always a surprise. I really don’t know what’s going to come out of my mouth.”

That’s such a great line!

I feel such an affinity with it. In recent years, another person who has kind of informed my thinking about laughter and poetry is Nuar Alsadir, who wrote Animal Joy: A Book of Laughter and Resuscitation. She’s excellent at analyzing laughter, being playful, and then also exploring the darker sides of things that we laugh at, which are not funny at all. She’s brilliant. She’s a poet and psychoanalyst who went to clown school. I completely adore her. She writes well about the freedom of finding one’s inner clown. When I am writing at my best, I’m usually quite close to my clown, who will produce things that are surprising or moving.

Interesting. It could be fruitful to look at Animal Joy close to The Crying Book as the flip side of the coin.

I would not object to someone teaching that course!

Mm-hmm. To return to Bill Murray for a second, his quote reminded me of this movie by Jim Jarmusch, Coffee and Cigarettes, which is a string of these absurd, black-and-white vignettes centered around a table and addictive substances. There’s one chapter called “Delirium” where RZA and GZA from Wu-Tang Clan are drinking herbal tea in this upscale teahouse, when suddenly Bill Murray enters from some other dimension like a short-order cook, drinking directly from a coffee pot. I think that cameo, where he’s plucked from some other environment, speaks to that slight undercut and surprising rhythm—or the “meaningful divergence” that Woolf might’ve employed—that elevates what would be a normal diner scene into something bizarre and funny. He certainly serves as a distraction or interruption to the reality that RZA and GZA are experiencing.

Right! That kind of absurdity is magnificent. It’s frequently an interruption to the status quo in a way that calls attention to the absurdity of the status quo, right? Poetry can be that intervention in language in a way that ChatGPT tends not to be. ChatGPT tends to produce language you can hear before it has been uttered. If more people were to practice acts of absurdity—listening to what language is actually being said, thinking critically about its true meaning, and then interrupting it with a matching absurdity—the world would become a very different, more livable place.

Interview Posted: January 20, 2026

MORE FROM DIVEDAPPER. (Drag left)