“I’m very much in love with this particular world.”

RIGOBERTO GONZáLEZ

Interviewed By: Kaveh Akbar

How are you? You’re in Puerto Rico now, right?

Yes. I’m sitting outside overlooking the water in my flip-flops. I love it. I come here every year.

Do you own a place, or do you just visit?

Well, I’ve gone back and forth on where to buy a place. It was either going to be here or in Oaxaca. I've been visiting both locations over the last ten years and I couldn’t make up my mind until now. I finally decided to buy a place here in Puerto Rico.

Is that a near future goal, or a down the road goal?

Well, I’m at the age where I have to think about retirement, if you can believe that. I have to think about where I want to end up in the world. And it’s not going to be New York.

You’ve certainly earned it as much as anyone could ever possibly hope to earn such a thing. You’ve earned it, but I think that everyone is going to be really sad when that happens.

I’m going to be one of those people who retires early too because—

Oh no!

I am. I sometimes look at other university professors who are in their sixties and seventies, and I’m like, "What the fuck are you guys still doing here? It’s not that great of a life to work at a university. There is an amazing world out there. You’ve done your work for the academy—thirty to forty years at a university is a lot. Now take that energy, that wisdom, that whatever gift you have, and take it somewhere where it’s needed. Or just chill out, retire, read some books, write some poetry, whatever."

I think there’s this sort of inertia where you just keep doing the work because it’s the thing you know how to do. It would be difficult to disrupt that inertia.

I guess. It’s the saddest of traps, one of the strangest deceptions that we have accepted in the United States along with this idea of the American dream. We were sold some bullshit and everyone still has this weird belief that if you’re not laboring or making money, then you are not existing.

Right, right.

Labor is important, but so is living. A very wise woman once told me to never confuse having a career with having a life.

Yeah, totally. I was just talking to Doug Powell about how, even in the writing world, if you talk to someone the question you ask is always, "Are you writing?" And the subtext is, "Are you a real writer?" Like if you’re not actively working on a major project, then you're just pretending to be a writer, or you're somehow a lesser writer. It’s a judgment, or a subtle way to shame someone into production. Even in our beautiful world of poetry we’re still imposing that sort of late capitalist pressure on each other, even on our friends, unconsciously.

Exactly. The unfortunate thing in our field is that we actually have products. And that’s what does it. If people do not see the product, then they can't imagine the labor.

Right, you are supposed to hide the labor.

I’m not one to talk, because I produce a lot of product, but it’s a very different sense of urgency for me, or a different relationship that I have to writing. I don’t know many people, on a personal level, who write and publish as much as I do.

I don’t know anyone else who writes as much as you do.

The one thing I learned a very long time ago is that I actually enjoy the process. I tell my students all the time: “Look, if you don't see yourself as a writer, then I’m assuming you don't see yourself as having a long-term relationship with writing.” And writing doesn’t always mean that the poem is finished—that’s just one moment in the process. It’s so much work. Sometimes stress. Sometimes heartache. A lot of thinking, and re-thinking, and writing, and revising and all of that is taxing, but the true writer welcomes those parts, too. You have to learn to love the process even as you begin to imagine a project, or poem, or story—even at that level you have to learn to expect a lot of disappointment and failure because that’s all part of the journey of writing. Otherwise, it’s hard for me to imagine a student sticking with it beyond graduation, when no one is waiting for them to write those poems or stories. Where does the motivation to write come from if it’s not from within?

Sure, sure, sure.

I try to teach my students that the writer’s journey is going to be a lifelong journey. None of this is just something to do until something else comes along. I always advise them, “Look, things come in, things happen, life happens, your path may move another direction and that’s fine. That’s just your journey. Everything is part of your journey as long as you make peace with it.” The blessing is still a blessing whether they are writing for five years or ten years after graduation, but ideally I want them to imagine being writers until the end of their lives.

Absolutely, absolutely. I can’t imagine why anyone would choose to be a poet of all things if they didn’t enjoy the composition process. It’s certainly not going to be for the money, you know? It’s not going to be for the fame, the critical notoriety. You can find all of these things in the business world, or in the professional world, or even in other aesthetic realms far more easily than you can in the poetry realm. So the joy has to be sort of intrinsic in the composition itself. It seems like a sort of prerequisite for this thing.

Exactly. And because we always talk about how writing is solitary, I advise my students to become part of a community so that they are not alone. So that they don’t feel they are writing in silence. This whole invisibility thing—we’re starving artists, we’re suffering artists—that just doesn’t sit well with me. I don’t like that. Why put the suffering next to the artistry when we’re going to suffer losses, we’re going to suffer heartaches in relationships. Do we really want to add more suffering to our lives? No! Let’s try to avoid that. The notion of being an artist or being a poet, somebody who participates within the community and who listens to the community, is very important, otherwise the community is not going to listen back. And I think that’s another valuable lesson that I’ve learned over the years—to be part of something larger than myself so that my failures don’t become amplified. Because there is something bigger out there, right?

Yeah.

Or so that even my successes don’t define me, because I don’t want to get to that level of arrogance, or reach a level of self-congratulation. I want to keep growing. I want to keep being curious. I don’t want to be all, “Oh, I’ve won these awards, I’ve done it, I don’t have to think again.” No! There is so much out there to mine, explore, investigate. As long as I am moving through the world, I will keep asking questions.

I think that’s beautifully said. And your reputation looms large in our community. Obviously your own poetry has won all the awards, but I think that you're one of our great advocates for other poets. I could name a dozen poets just off the top of my head who came into the community because you had blown your trumpet about them. You're a poet who has absolutely amplified a community.

That’s a value that I learned from my literary ancestors. I understood that there were so many limitations they had, and I acknowledged that I had so many opportunities that they did not have. And so when I see the next generation of young writers I say, “Look, you're going to have access to things that I didn't, so what are you going to do with that? How are you going to pass it on, or pay it forward, or use that as a tool to benefit others?” It seems like it’s all common sense, right? But many don’t think that way. I don’t want to turn my attention to negativity. I try to stay away from that. A long time ago, I decided as a book reviewer, as a critic, as an advocate, that I was going to try not to focus on things that were not working or people that were not helping. They are small, they don’t matter.

Right, I agree.

But the reason I keep going back to this issue of community, and of becoming a good citizen for the community, is because I sometimes see people falling into a trap of wanting to just accumulate rewards for themselves. You can’t just tell people don’t do that, you have to be a role model. You have to show them what it's like to not make those narcissistic decisions. And so I feel as if that’s what I’ve done with my career. When my community celebrated me at Poet’s House, I was so happy to see my students there. The next day I taught class and I said to my students, “You know, I want you to recognize one thing: that that tribute wasn’t in gratitude for something I did in the last month, or the last year, or the last decade. That was decades of work. That’s decades of commitment.” In other words, that’s a lifetime of cultivating goodwill. I wish the same for my students.

I’m only in my mid-forties. I still have a couple of years ahead of me and so now I have a new challenge: What else can I do? What more can I do? Hopefully inspire other people to do the same things. When I was in my twenties, there were so many uncertainties and I felt like I was keeping my dream very small, or smaller than I think it should’ve been, because I didn’t see those examples around me. I didn’t see those opportunities for people like me. I say that as a Latino writer, as a queer writer, as an immigrant writer. So I kept my dreams small, like, "If I can reach this, then I’ll be fine." What ended up happening was that when my dream was made bigger through recognitions, publications, and acknowledgement from people in my communities. All of these things made me realize I had much more to offer. And I appreciated that, but it also helped me see everything as a blessing instead of feeling entitled to any rewards. I still get embarrassed when I see people behave like that around me. It’s like, “Who taught you? Who mentored you? You are not listening. You are not paying attention. Those things are very short lived.” What sustains a writer should be knowing that their work is saving lives, or teaching people, or reaching someone in the darkest of moments of their life. How the work resonates out is what’s important, not what the work brings in.

That’s beautiful. That’s such a healthy orientation. I think that if you could bottle that and give a dose to every writer in America, we would be a much less neurotic people.

Some of us need to be force-fed that.

My dad came to this country in his twenties and spoke not a word of English. He had a duck farm my whole life, and he woke up at four o’clock in the morning to work at this duck farm every day. So I believe that if I am going to be a poet, then it has to be bigger than just me sitting around and writing poems. You know what I mean? After the sacrifices he made, the sacrifices my mother made with him. You write about your parents' experience as growing up in extreme poverty as migrant workers, and I wonder if there’s maybe some of that there, too?

Absolutely. You know, every time I receive any kind of acknowledgement, I always remember my parents. I always say thank you. I don’t have them anymore, but I like to believe that everything they did was also part of my journey. Including making choices like coming to the United States when I was ten years old. Coming from Mexico I didn’t speak any English. I had to learn it. And I think it actually was Eduardo C. Corral who told me this beautiful sentence that I now use often, "We are who we are because of what our parents did for us and because of what our parents did not do for us."

And what I learned as an immigrant and what I learned from my immigrant family is this—what I do is going to resonate and matter to many others. So, as a writer, whatever I do, I do it knowing I’m upholding an important value my family had. That we have to be part of something bigger than ourselves. They were union members, so they were always on strike, and always in marches. I grew up seeing this activism. When I was a child they would take me along to boycotts and labor strikes, and what I saw was the sacrifice that came with that. They were not earning money, but they were fighting for something that was eventually going to change everybody’s lives for the better.

Sure.

I still think that’s the way it is. That’s the only way a person can do something: as a collective, as something communal, as a group, as a community. We can make change happen faster.

Yeah, absolutely. I think that’s so poignant and I love the way that the experiential facts of your life color your creative orientation. That’s a really beautiful connection that I don’t think all artists can necessarily have so consciously.

I made a good choice. Family is important to me. Art is important to me. It’s what I learned to love. It’s my appreciation. My family had a way of creating change, of being part of a momentum. At nine, I discovered mine—language. And that’s important.

Yeah, yeah. You’ve said, “Perhaps because I grew up in extreme poverty, I reach for the shiny things in real life—ties, shoes, cufflinks.” I’m curious about whether or not you see that extending into your creative life, or into your aesthetic orientation, or into the actual content of your poems. That sort of reaching for the shiny things.

Yes, it’s interesting because if you ever saw a picture of my apartment, I think you would understand so much of how it mirrors my poetry. I collect so many things. I’m actually going to move soon because I don’t fit anymore in my apartment. I have so many things—paintings, pottery, everything that reminds me of Mexico. Very garish things.

As for why that is, well, a couple of things—one is that I grew up with so few possessions. When I came to the U.S. my parents asked me to only bring three things. We traveled by bus so we couldn’t take much. We got to choose three things. That was it. We lived in this very poor neighborhood in the city of Thermal, California, where we had an old T.V. with no antenna, so we only had two channels. That’s how we entertained ourselves for years and years, with only two channels on our T.V. In so many ways I grew up with this sense of knowing that I had no choice but to live with limitations, or to live with limited choices. Poetry, for me, offers such richness. Its possibilities are endless.

When I was a young man trying to understand my place in the world, my family could not really help fuel this sense of “You can be whatever you want to be.” That just wasn’t instilled in me as a young man. My family was illiterate. I had to help them through understanding this and that when a piece of paper came through. That was tough, but I learned to see the differences between what are actual stumbling blocks beyond my control and what are choices I could make to improve my own situation. I discovered, for example, that poetry allowed me that expansiveness, that landscape that I wanted to build, that I wanted to furnish, that I wanted to enrich and cultivate.

More recently I've been writing longer and longer poems whenever I sit down to write. I keep gathering, and collecting, and owning, and claiming because I had so very little. For a long time I thought that that was going to be my fate and that I wasn’t going to have very much. I changed that.

Now I’m working on my next memoir, which explores masculinity and manhood. I was talking to my brother on the phone about this, about this memory that I had when we were working in the fields—my grandfather, my father, my brother Alex, and I. Quitting time came, and the car wouldn’t start. Everybody had gone home, and we were stuck there in the middle of nowhere, this was before cell phones, and we were far removed from anything. It was just the four of us in the middle of the desert with no way to get home and no way to contact anybody. And my father was so distressed that he began to cry because he felt like he had failed us because he had bought this cheap car. Because we couldn’t afford anything better than the cheap car. And the car had betrayed us and left us stranded there. When I saw my own father crying, I had to man up a little and tell my father to stop crying. “Everything is going to be okay, don’t let my grandfather see you cry. Don’t let your father see you cry.” I said that to my own father. “Alex and I, we’ll go to the road and we'll wave down a car.” So I kind of took control a little bit there. I was saying to my brother, “You know that was a moment of such hopelessness for our father because he understood very well what little he did have and everything that he did not.” But it was different for us, his children. I was already thinking about college at that point, so I thought, “That’s never going to be me. I’m going to have so much more because of my father.” But at the moment all I had was a little bit more faith and hope than he had, and I needed that to help him get through that day.

I remember all that when I write and I just want to include everything. Everything just comes in. Everything becomes part of the story and everything surrounds the story of my father, the story of my mother, the story of my grandparents, the story of me as an immigrant kid from Mexico, and it makes our stories larger and part of something more significant. Although, again, to reiterate, we are significant already. But to become more significant is also important because now we are sharing, now we are participating, now we are interacting, and now we’re no longer invisible.

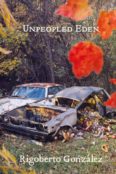

That’s staggering. If you could see me right now you'd see that I have literal goosebumps. What a staggering moment. The ambition of all great stewards is to leave things better than they found them, right? One of the great images from Unpeopled Eden that I will never ever ever forget as long as I live is the last image in “The Border Crosser’s Pillow Book"—the gold-plated kidney stones being worn as teeth. I wish we were Facetiming because I got goosebumps again just talking about it. It’s that powerful of an image. It will never leave me. I mean, here is this really terrestrial, ugly thing, a kidney stone, but even that is sort of being cast into this kind of opulence. This kind of glittery, beautiful metamorphosis.

It’s seeing the value of things that have been deemed as having no value. Seeing significance and relevance in people that have been told that they have no relevance, significance, or importance. That’s something I also grew up feeling as a farmworker. My family and so many of my family members were undocumented. They were also invisible and they had to stay invisible. They didn’t read, or they didn't know how to read, or they didn’t speak English—there are so many ways in which they were just not seen as fully realized human beings even though they were.

I go back to those early memories and that’s why I write so much about my family. I want to keep emphasizing the fact that these were very complicated lives. These were very multivalent experiences that people have refused to see because they don’t have this or they don’t have that. Well, they may not have those things, but they have so much more in other ways if you just really look and see. I grew up and not everything was pretty, of course, there were some hardships. My next book, my memoir, really explores that honestly. And the next book of poetry is looking out at the larger landscape, looking at the history of America. I’m very interested in the ways certain narratives have gotten buried, or lost, or are being submerged because there are other louder narratives out there that have been deemed more important.

Sure.

I’m interested in excavating and unearthing these other narratives and just singing their praises, or at least bringing them out into the open. so that at least people will recognize that they existed, that they were. That’s something I’ve been doing all along, really. You know, from my first book of poetry I’ve been looking at workers. I guess that’s always been my mission and my aesthetic and I’m building on that and finding more complicated angles to mine in that territory. I don’t want to write the same poems and I don’t want to feel like I’m writing the same things, so this keeps me going. It’s funny, but I never thought that I would ever be thinking—I’m finishing up my 19th book, and I’m already thinking of the 20th. While I've been here, I’ve already thought about books 21 and 22.

Wow.

They are already in the computer files and in my memory banks, so I already know what I’m going to do next and that’s exciting. I’m always a little scared because I’m finishing up one book and I always get this anxiety during the last couple of pages like, “Oh my God, what am I going to do after this?” But as soon as I’m done, something else pops up. I never thought that I’d ever be talking to somebody and saying, “Yeah, my 20th-something book.” Never. I never thought I’d share my first book. So it feels really great because that at least gives me a sense of knowing that I’m still very much in love with what I do, which is to create, and to imagine, and to think, and to critique.

I’m very much in love with this particular world. I’m not that enamored with the people, I’ll tell you that. My students always ask me about who I hang out with. They ask, “Who are your friends?” And I say, “You guys.” I only hang out with my students, that’s it.

Aww.

They are blown away by that, but I’m telling the truth. No, I don't hang out with other writers. I stopped doing that a long time ago because it’s a little tough, especially in New York. People are busy and stuff. Plus I love talking to my students. I want to be around people whose curiosity is still taking incredible shape, and my students are so inspiring. I go to workshop and we talk about poetry. It’s the only time I talk about poetry anymore. I tell my students, "Talk about poetry now because when you leave here, you’re not going to find many opportunities." And some students come back years after graduation and they say, “You were right.”

Eduardo C. Corral is my best friend, so he’s one of the few professional writers I talk to on a regular basis. Other than him, I prefer to talk to my students. That energy is still there and every time we workshop I feel like something incredibly special is happening. This world of language is still very much alive in my students and it has so much potential. I want to continue to be a part of it.

Interview Posted: March 27, 2017

MORE FROM DIVEDAPPER. (Drag left)